A Short History of Kiln-Cast Glass

Glass has always carried light across human history — from the stained windows of cathedrals to the prisms of science. But it is only within the last sixty years that glass has been freed from industry to become a fully personal medium of sculpture and expression.

Sam Herman, Untitled, blown glass, signed and dated 2013, 37cm (14.5in) high, Private Collection

Photographe: © Sylvain Deleu 2018

From Factory to Studio

The studio-glass movement began in the early 1960s when artists such as Harvey Littleton and Dominick Labino demonstrated that molten glass could be melted and formed outside a factory. Their 1962 workshops in Toledo, Ohio, gave birth to the idea of artist-as-glassmaker.

In Britain, that idea took root through Sam Herman, an American artist who studied under Littleton and moved to London in 1966. At the Royal College of Art, Herman founded The Glass House in Covent Garden (1969), where artists could blow, fuse and cast their own work. His example ignited a generation — yet it was only one of many seeds.

While Herman’s furnaces burned bright, other artists were quietly exploring glass in the kiln, where heat works slowly and gravity becomes a collaborator.

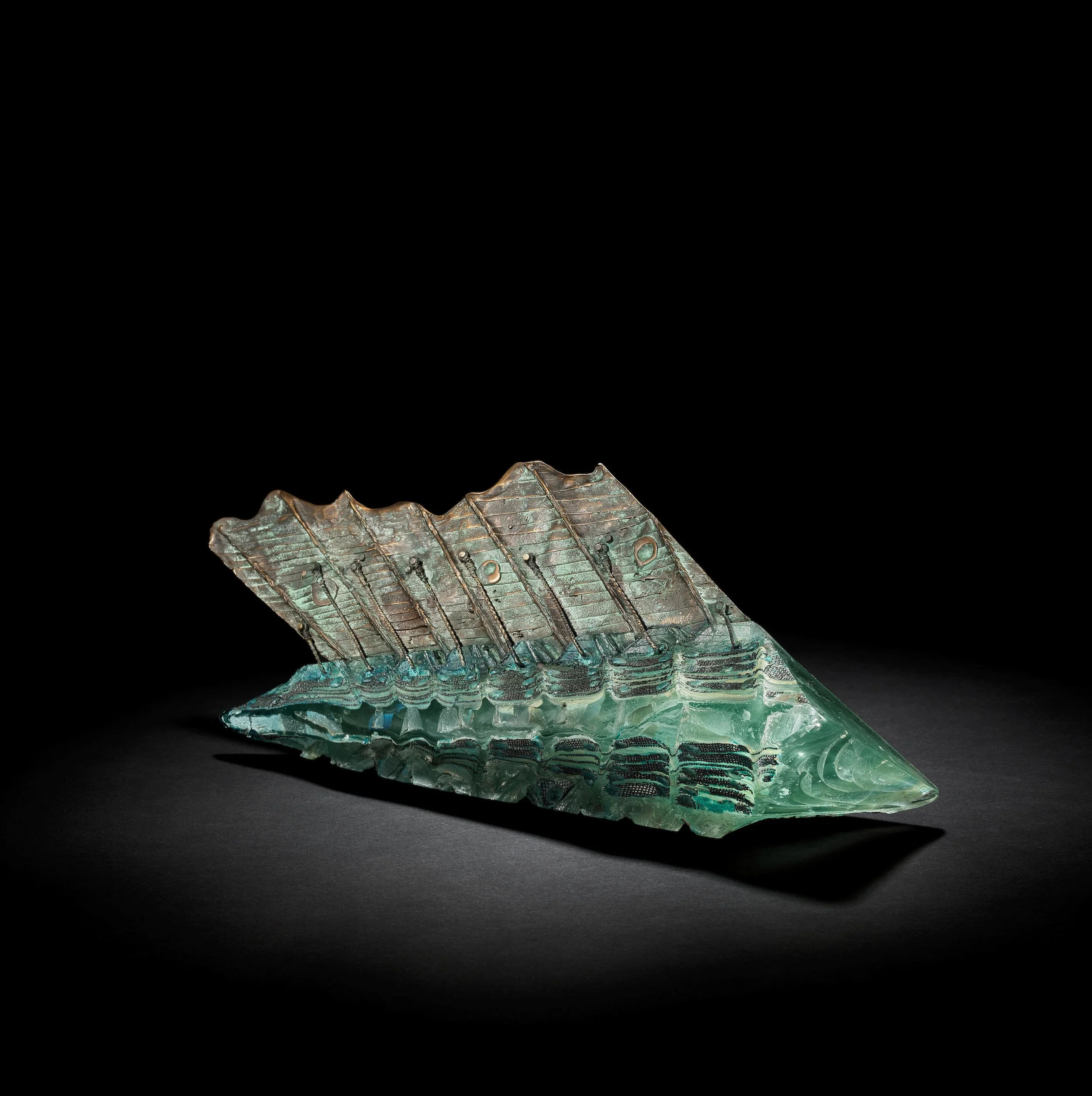

Keith Cummings 'Flagship', sculpture, 1991

The Language of the Kiln

The shift from blowing to kiln-forming opened new possibilities: fusing sheets, slumping over moulds, or casting molten glass into refractory forms. This quieter revolution drew on ancient techniques but was renewed by twentieth-century research.

In Britain, Professor Keith Cummings at Wolverhampton University became a key figure in this evolution. Through decades of teaching and writing — notably A History of Glassforming and Techniques of Kiln-Formed Glass — he mapped the ways temperature, time and material can be used as creative partners.

Cummings’ own pieces, such as Watercolour and Red Stack, combine architectural precision with painterly sensitivity. Many of today’s artists, in the UK and abroad, acknowledge his influence in understanding how glass can hold both structure and spirit.

‘Still Life With Corn’ Colin Reid 2017

Optical Sculpture and the Language of Light

Among those inspired by Cummings’ teaching was Colin Reid, who, from his studio in Stroud, pioneered the use of optical kiln-cast glass. Reid’s work involves building complex moulds, casting crystal-clear glass, and then grinding and polishing the surfaces to reveal internal landscapes of reflection and shadow.

His sculptures, such as Gatekeeper and Loch Moidart, are collected by museums around the world, including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Reid’s practice showed that cast glass could be as monumental, precise and emotionally resonant as bronze or stone.

But he is one voice among many. Over the same decades, artists across Britain — from David Reekie to Angela Thwaites, Joseph Harrington to Cathryn Shilling — developed their own vocabularies, proving that kiln-formed glass is a plural art, not a single lineage.

Alongside them stand countless other makers — teachers, technicians, experimenters — whose furnaces and kilns together form the living ecology of glass in Britain.

Kiln-cast glass, at its heart, remains a shared endeavour: a conversation between fire, material and imagination. Continuing the Conversation

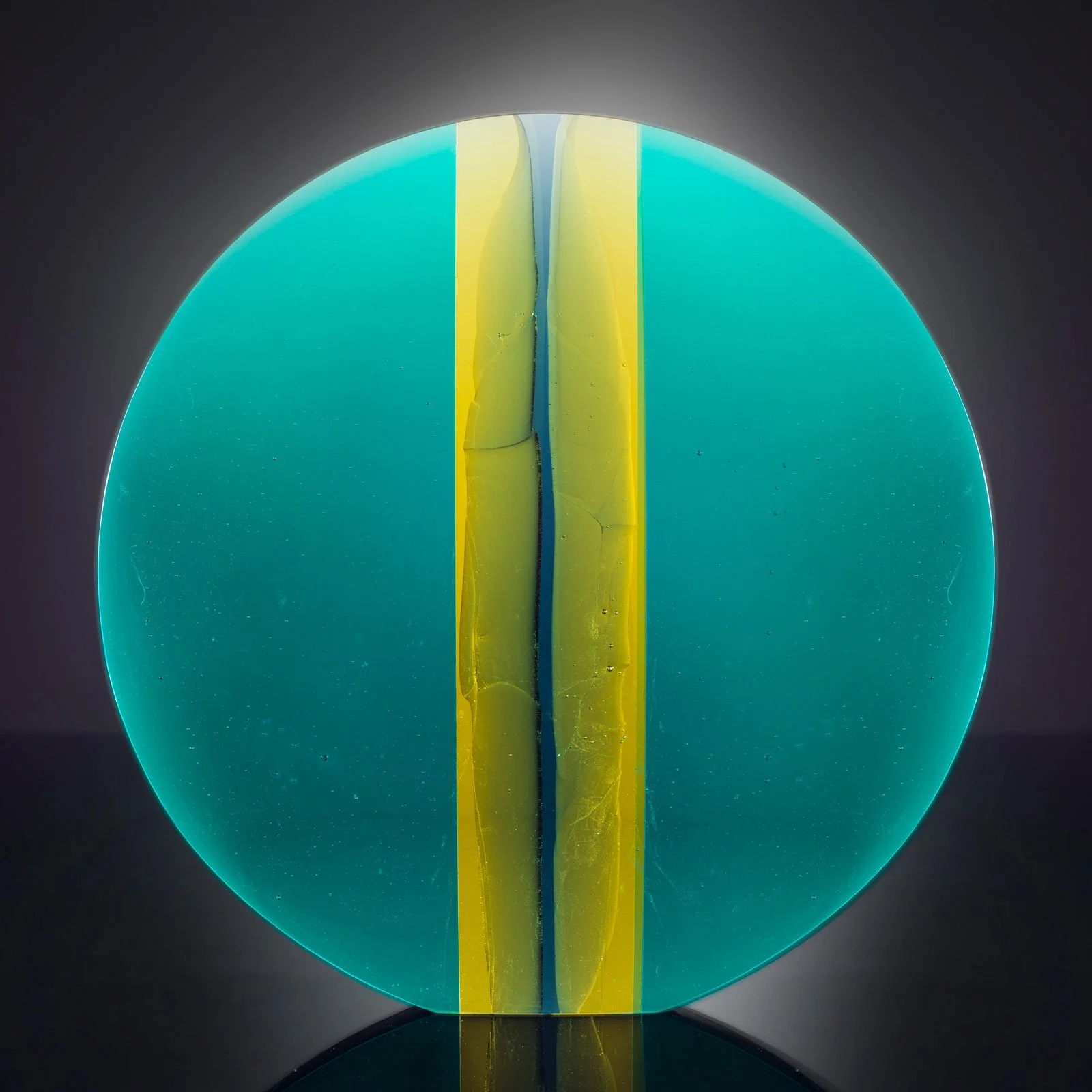

Fiaz Elson, Creative Director of The Glass Foundry and former senior assistant to Colin Reid, represents the next movement in this conversation rather than a conclusion to it.

Her practice explores the interplay between strength and delicacy, transparency and concealment — themes shared by many contemporary glass artists. Works such as Osiris and Rheiopolis balance disciplined technique with an intuitive sense of emotion and form.

At The Glass Foundry, Elson collaborates with artists, designers and architects to test new ideas in casting, colour and light. The studio’s ethos is one of continuity through openness: honouring those who came before while inviting others to shape what comes next.

Ocean - Fiaz Elson 2022